Decoding Hot Girl-On-Girl Action

The Peculiar Problem Of Politics, Pornography And The Ass-Kicking Babe

by Lisa Jervis

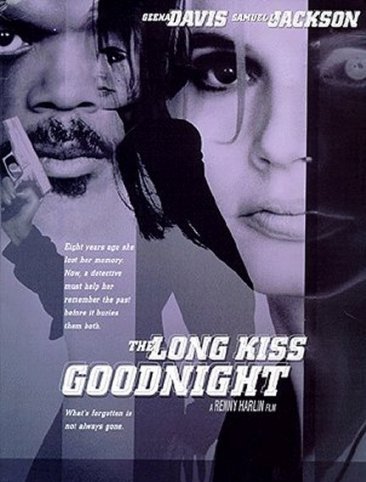

Hot chicks kicking celluloid ass are far from a new phenomenon. Varla, the outrageously busty, menacingly sexy antiheroine of Russ Meyer's seminal 1965 Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, isn't even the first in a long line of killer babes that includes the original Charlie's Angels, Alien's Ripley, Terminator 2's Sarah Connor, The Long Kiss Goodnight's Charly Baltimore, Buffy of vampire-slaying fame, Out of Sight's Karen Sisco, any number of Pam Grier characters and, of course, Thelma and Louise.

The past half-decade or so has yielded a particularly abundant crop: Tomb Raider's Lara Croft, Alias's Sydney Bristow, the new Charlie's Angels, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon's double whammy of Yu Shu Lien and Jen Yu, and, most recently (and, perhaps, spectacularly), Kill Bill's the Bride. Such images are becoming both more common -- just look at the pileup since 2000 -- and more mainstream. Varla and Foxy Brown kept company in the ghetto of exploitation, but Lara, Buffy and Syd have moved well beyond their culty roots. And as for Nat, Dylan and Alex, well, Charlie's Angels and its sequel grossed more than $490 million worldwide.

To put it bluntly, there's something going on in the culture that makes the Ass-Kicking Babe such a hot property. I would love to argue that we're seeing a feminist influence on the way that femaleness can now be combined with power. Unfortunately, I can't: These contemporary babes' uberfemininity combined with competence in hand-to-hand combat may be refreshingly free of Varla's dubious "my sexuality is out of control and can kill you" appeal, but that doesn't mean it equals a feminist statement. It's a cliche at this point to even mention the way that Lara Croft, in both her pixelated and Angelina Jolie incarnations, is little more than silicone-injected eye candy with which to decorate action sequences in a new way (or, conversely, that action sequences are simply replacing Playboy-style cheesy canopy beds as a new backdrop against which to view silicone-injected eye candy). She may be the most extreme example, but all these ladies traffic in a similar appeal: the too-obvious use of stereotypical ideals of attractiveness in order to camouflage their physically threatening nature.

So while this puts quite the fly in the feminist ointment, I'm not ready to count those AKBs out as my allies. Representational violence, for all its flaws, does have political promise. When we see fictional violent women, it forces a shift in our ideas of what women are capable of both in real life and onscreen. As Martha McCaughey points out in 1997's Real Knockouts: The Physical Feminism of Women's Self-Defense, "Self-defense disrupts the gender ideology that makes men's violence against women seem inevitable." Thelma and Louise, for example, presented a vision of behavior that was both inspiring and deeply satisfying to a large number of viewers: Someone rapes you? Shoot the asshole. Criminally underseen independent films like Freeway and Girls Town went a step further to explore not just the power of fighting back, but the potential effect of conscious alliances among women willing to do physical harm to rapists and other abusers.

Then there's the way in which filmic violence acts as a response to the history of represented femininity -- it asserts that our bodies are about more than passivity and display. Plus, it's an expression of anger that is all too often culturally trained out of us. Last but certainly not least is another of McCaughey's points: " The presumed inability to fight in part defines heterosexual femininity." As should be obvious, anything that can fuck with the culturally normative straight girl is a useful tool.

But, as should be equally obvious, cultural norms tend to fight back. It's no coincidence that the recent depictions of violent women onscreen have been accompanied by a refiguring of the catfight. Women are fighting more on film, yet they are increasingly fighting not male evildoers but one another.

Furthermore, such images take the AKB's sexualization to a whole new level. In the same way that "lesbian" porn made by and for straight men (you know, those movies featuring fake-titted high femmes with long, long fingernails) turns the notion of an autonomous female sexuality into a display dependent upon and intended for male consumption, today's increasingly common type of filmic catfight turns women's anger and violence into a show for the boys.

This is partly due to the problem I've already mentioned, that any woman with the physical characteristics necessary to be entrusted with headlining a Hollywood film will generally be considered "hot" by most male viewers; however, that's far from the end of the story. Girl-on-girl violence borrows not just its raison d'etre but its visual cues and costumes from the world of pornography. Evidence of this connection abounds. My video store has a shelf full of bikini-wrestling titles (FYI, it's right below the Russ Meyer section and to the left of the actual porn), which feature '80s-style starlet wannabes in "bouts" choreographed to get legs splayed, crotches grinding and bikini tops ripped off. AKBs love to do things like jump from rooftops while wearing stilettos, and their directors love to include foot-level closeups of the landing. In the neonoirsploitation Wild Things, Denise Richards' attempt to drown Neve Campbell, her partner in crime (and threesomes), culminates in face-caressing, finger-sucking and hot-and-heavy smooching.

The result is hobbled potential, a visual library with the political potential leached out in favor of cheap sex. What could emerge alive and kicking to channel women's anger ends up stillborn. Nowhere is this clearer than in the phenom's most prominent example, Charlie's Angels: Full Throttle. In their second outing, Nat (Cameron Diaz), Dylan (Drew Barrymore) and Alex (Lucy Liu) find themselves up against former Angel Madison Lee (Demi Moore) -- and pornographic iconography pervades the film from its opening scene to its, um, climax. The opening set piece alone -- Diaz, dressed in pigtails and a white fur-trimmed snowsuit, spouting faux-naivete in a Swedish accent and riding a mechanical bull; butch, card-playing Barrymore; Liu clad in a leather catsuit and stilettos -- would be porno enough to make my argument. (Let's not forget that Swedish girls are a porn class all by themselves.) But that is literally just the beginning. We get Diaz and Moore in bikinis, leaning in to each other in an almost-kiss. We get Moore in a fur coat, bra and panty set, heels and a gun. We get the Angels fighting their final confrontation in a leather jacket and pants with a studded belt (Barrymore), low-riders with an off-the-shoulder midriff shirt that laces up the sides (Diaz) and a tiny skirt with fishnets and a little leather top (Liu).

But it's not just the costume choices that echo dirty movies; the film's precisely choreographed nature (featuring fight scenes that mimic sex acts) and its reliance on set pieces -- including one that puts our gals on the stage of a retro-Teutonic burlesque strip bar -- reveal a structural similarity to porn that can't be ignored. The "plot" here is nothing more than a thin glue to hold these pieces together so audience members can pretend they're watching for reasons other than pure gratification of the senses. And then there's the money shot: When Moore is finally vanquished, she falls through the floor of the final battleground, breaking a pipe as she goes and causing a spectacular ejaculation of water.

By comparison, Kill Bill has genuinely entered new territory, managing to dodge many of the gendered pitfalls that plague other AKB vehicles. Most superficially, the styling choices make clear that this is no jigglefest. While of course Uma Thurman, Vivica Fox, Daryl Hannah and Lucy Liu are still Babes, Tarantino doesn't put them in anything resembling the Angels' skin-baring low rider/halter ensembles or Alias's undercover-girl fetishware-inspired getups. Instead of stilettos and skintight leather pants, there's an iconic yellow tracksuit. When the Bride (Uma Thurman) fights, she gets disheveled, dirty and bloody. She's more about acting than appearing. (The Angels, even when they're acting, are really just appearing.)

Perhaps most refreshing is the way that gender often doesn't matter. It's ridiculous that we have to feel grateful for this at all, but when gender so consistently determines the range of female characters' motion and emotion, a celluloid scenario in which this isn't the case is to be treasured. Take, for example, the Bride's encounter with famed swordmaker-turned-sushi-chef Hattori Hanzo. A lifetime of filmgoing has prepped the viewer for a "what's a nice girl like you doing looking for a sword like that?" reaction to the Bride's request for Hanzo steel -- but it never comes.

Furthermore, Kill Bill: Vol. 1 successfully gets at some of the powerful potential that screen violence holds. As the Bride lies supposedly helpless in her hospital bed, attendant/rapist Buck prepares to pimp out her unconscious body as he has presumably been doing without consequence for years; instead of a cheap thrill, the rapist/customer gets a grisly death, as does Buck. And then there's schoolgirl-turned-assassin Go Go Yubari. In her pigtails, short skirt and kneesocks, she embodies a pornographic icon even more common than the Swedish girl. The film itself, however, refuses pornographic logic even as it deploys the iconography: Witness Go Go sitting at a bar engaging in a grotesque mock flirtation with a drunk guy who's drooling all over her. After she not-so-coyly asks him if he wants to fuck her, and he admits that he does -- perhaps thinking that she's making an offer, as she would be if this scene were taking place in a porno -- she sticks a knife in his gut. Like Thelma and Louise's rape-revenge shooting, this is both a powerful reply to film history and a viscerally satisfying moment for many in the audience.

Unfortunately, Vol. 2 manages to turn the Bride into a different but equally overused feminine archetype -- not porn star but fierce mama, fighting to protect her family. The film's second half reveals that it was the Bride's thwarted maternal instincts that set in motion the chain of events leading to her desire to kill Bill in the first place; its coda ensconces her and the kid in a tidy little mother-daughter dyad, sans threatening violence. It shores up this use of the maternal by reproducing the powerful fiction that women share a transcendent bond of sisterhood stemming from their potential to bear children: Just after the Bride has discovered that she's pregnant, a rival assassin shows up to prevent her from finishing her next assignment. The Bride saves her own life by pleading for that of her unborn child.

The simplistic questions to ask are if these images make for good role models, and whether they're good or bad for feminism. But what we need aren't better role models, or images that can easily be labeled "good" or "bad." Once pornographic iconography thoroughly saturates women's film violence, we'll be stuck with that tired old depoliticized sexualization clouding our vision whenever we watch it. What we need is substance beyond the pornographic. What we need are conceptions of female violence that preserve the potential of the threat that our rage and our power represent.

© Lisa Jervis 2004. Click here to read more of Ms Jervis's articles. Visit the Alternet.org media/culture site, where I found this piece, for more sharp writing on interesting topics. :)